Table of Contents

Brian Hodge is no longer qualified for the first job he held in his dad’s yard, Kruse Lumber, of Rochester, Mn. At age 14, as the youngest, skinniest soul on the site, he was delegated to climb atop the railroad cars delivering redwood and pine and toss the boards down, one by one.

Brian’s added a few inches and pounds since those days, so scrambling is no longer on his list of duties. But on the way to becoming president, darn near everything else has been. And that’s fine, he says, because, fighting the silver-spoon image of the boss’s kid, he was handed every job in the place, starting with the broom. He worked summers during high school, returned after college, then spent the past 41 years starting off in the warehouse, then the retail floor, on to marketing/advertising and sales, then assistant store manager, manager, and GM before assuming the president’s chair in 1994 as his father, who died that year, had eased his way out.

Not always willingly. “Dad’s style was, ‘Nothing’s handed to you: You work for what you get.’ Which was a blessing,” Brian now declares, after having served in nearly every spot on the payroll on his way up.

The company actually was launched back in the horse-and-buggy days of 1915 by H.J. Kruse, who relocated to Rochester after gaining a favorable impression of the city during a Mayo Clinic visit. Various owners followed, culminating in Brian’s father, Harold. What never changed, however, was what Brian identifies as “the good work ethic. The promise that we would provide our customers a fair deal.”

Did he always get a fair deal, himself? Sometimes it took a little persuasion. “For a long time, Dad wouldn’t let go; it wasn’t easy for him to do. He micro-managed. He couldn’t grasp that younger people needed the chance to take on responsibility and be accountable.

“An opportunity came up in 2009 to take on extra business, but we needed a couple of things to be able to get it. I talked to him about it, and it was ‘Absolutely no!’ We had some words. So I spoke to our accountant: ‘I need to manage, or get out.’ ‘Wait, wait, I’ll talk to your dad,’ he offered. And Dad conceded: ‘You’re right. You need to make decisions.’”

So Brian did just that. “It was the dumbest mistake I ever made. It didn’t pan out. It gained us lots of business, but at much lower margins. It was a learning experience,” he can laugh today.

“Fundamentally,” he’s learned, “we simply need to stick to our mission of providing lots of value—to be very service-driven. Our customers expect high-quality products and lots of service. They have confidence that, if anything happens—if a product fails—we stand with them to resolve the issue. And not only product replacement, but, what’s less common: money toward the labor, too.”

Kruse’s business is almost entirely with the pros—contractors building custom homes, remodeling them, and those involved with commercial projects. That business decision was made in the face of two existing Menards and an inkling that other big boxes were ready to pounce on secondary markets, such as Rochester. “We could try to be everything to everybody, or concentrate on serving the pros vs. walk-in trade. So we took ourselves out of retail, allying with LMC for commodity products—a no-brainer for us.”

Risky? Not really. “We never had any commercial accounts until five years ago, but then we had an opportunity to hire a person who came to us with very good relationships with the supes and foremen. He’s doing a bang-up job.”

A reminder, readers: Rochester isn’t your typical 100,000-population city. Diversity isn’t a big factor. It’s actually a company town (well, two big-deal companies)—Mayo Clinic and IBM—with a huge white-collar presence. “That’s a big market for us,” says Brian, “and it’s not nearly as up-and-down,” buffeted by the economy, as many.

The doctors and fellows at Mayo build anything from $300,000 to $2.5 million homes, he reports, all via the same high quality of builder, who take pride in what they do (remodelers, too). And that,” he declares, “is our market: large custom homes and large remodeling jobs.”

The problem, in his view, is with land—or the lack of it available for development, to be exact. Before the downturn in the early 2000s, lots were snapped up but then remained undeveloped during the drop. “So there are no large tracts available now; they’re too fragmented: maybe 20, 30, 40 homes.”

But a bigger problem looms, and that’s the labor force. Again, the lack of it. “Our industry needs to do a better job of getting across what we do, to bring Millennials in. We need to start promoting ourselves as more attractive, to support jobsite development, new home construction. To take pride in providing people with their new homes.

“But,” he laments, “our industry is old school, slow to change. Today those 20, 30-year olds have never swung a hammer. Yet, they have certain expertise: in sales, in marketing. They lean on the Internet to discover what’s got the bells and whistles. We simply have to do a better job.”

Why do Kruse’s customers stay loyal? It’s back to that all-important labor force. “When you look at providing service, it comes down to the quality of our people. People who are hard-working, decent, full of integrity. People who want to help you and stand behind you. That”—he declares—“is what Kruse is.”

After all, he continues, “If you do, or sell, something unique, other independents are quick to pick up on it. So the difference between us and other yards is the quality of our people and the quality of our products. We sell only the highest grade of lumber (which actually saves the builder time and money in the end). We could offer, say, inexpensive doors, but we stock better product. Others say they’ll build you a $250,000 house, but that means reining in the costs, and those builders buy (products) accordingly.

“Here, we treat every day as the first day, proving ourselves over and over again.” And the way to get across the message is by example. “When something comes up—if there’s an improper install that’s out of our control—if the builder has to absorb it, we say, ‘Let’s help him out.’ I hear, ‘We never used to do that,’ so I tell them, ‘Now we do.’ I hear, ‘Brian, you don’t have to,’ but I say ‘We’re in it for the long run.’”

To stay in the game requires marketing, of course. And social media plays a part. “Facebook is our primary tool, along with LinkedIn and Instagram. This year, we hired a young man who knows the stuff, to create excitement and keep it going. Maybe it doesn’t reach our older pros, but there’s more action from the younger carpenters and trimmers.”

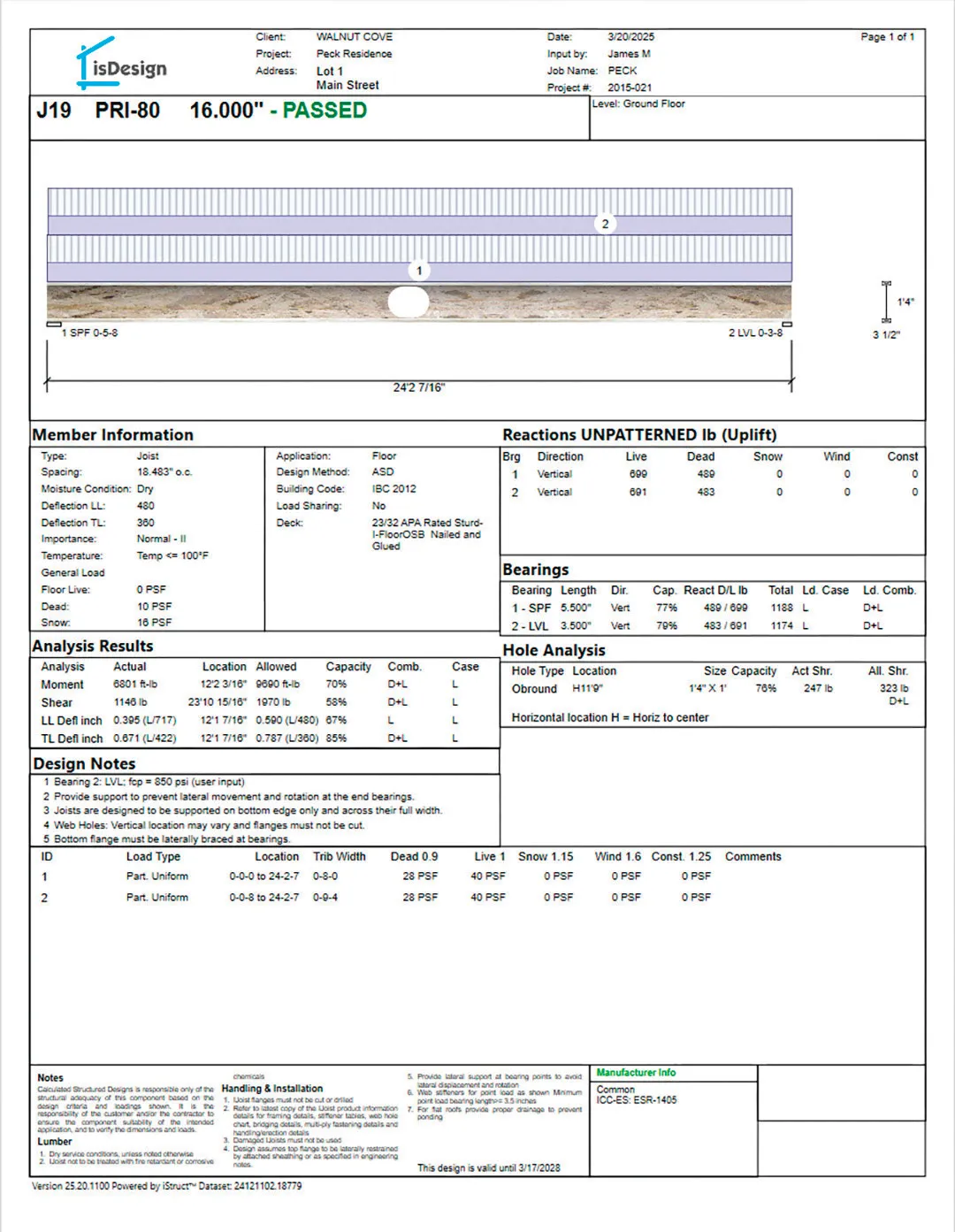

Kruse also keeps its message fresh through contractor breakfasts. (Brian tried lunches, feeling the mid-day break would be popular, but no; the pros made their early AM preference clear.) The next will be hosted by LP to introduce its new Legacy subflooring. Kruse also participates in LMC roundtables, from which Brian came away with new respect for OTIF delivery. “We now have meetings about the metric: on-time, based on what we promised, and we’re hitting 95%, company-wide: purchasing and sales as well as delivery trucks. We use this as a strong selling tool.”

Did the recession leave an impact on this white-collar town? Yes, it did. “But we’ve always been conservative here at Kruse. In 2002-2003, people urged us, ‘Get bigger! A second yard!’ but I told them, ‘No, not until I get this operation running the right way. I don’t need to add any more problems.’

“Then, during the downturn, the chains left. It was a little scary, but we rode it out. Today, it’s just family-owned independents, and we each have a different customer base.”

Remodeling helps, too. “People are very much into it, as they look at the high cost of building today—the high cost of materials, development, fees. Instead, it’s ‘I like where I live.’ The classic older homes. Remodelers like that they can work in just a certain quarter of the city, not have to move around, for when they’re out there, a neighbor will come over and say, ‘Let’s talk.’”

The town that Mayo built is getting an enormous boost as the venerable clinic expands big time, in a 20-year, $6-billion initiative involving the state as well as the clinic itself. The challenge, as Brian sees it, will be to provide affordable housing for the 30,000 jobs it adds. “You still have to bring people in and house them.

“We’re getting involved in the project as much as we can, going to meetings and dinners,” because he knows it pays off. Reversing the phrase about “…it’s who you know,” Brian states, “It’s who knows you.”

Twenty years: Who’ll be running the outfit in that distant future, Brian? “I have two sons in the company—one in inside sales and the other as distribution manager. But”—he emphasizes—“in today’s market, it takes a collective group to bring a company forward, not one or two individuals, like back when I had that opportunity. So, our two boys, sure, and give them as many experiences here as possible to assure a well-rounded future.”

But Brian’s wisely thinking even broader. “I formed an executive committee (six members, including my sons) to take the next leap. I want them to look at the big picture five, ten years out: Where and how is Kruse’s market changing? Talk, discuss it, put some things in place. We have the advantage of being a smaller, middle-size company, so we can move fast, be nimble, not wait around to check in with corporate. I’m happy to be on the sidelines, a consultant. I want these six to get excited—‘Brian’s allowing us to do different things!’—and find those opportunities. New blood.”